Stranded on a stretch of highway between Baker, California, and Las Vegas, both of us noticed the SUV pull in front of us on the side of the road. It was 107 degrees outside, in the middle of the afternoon, and we had just commented on how this pull-off area smelled like a sewer. A few feet to our right we could see that the road’s shoulder was littered with plastic soda and water bottles, and all of them had the same color fluid in them, baking in the sun, leaking into the ground. Drivers had apparently used these bottles to empty their bladders, then tossed them out of their vehicles, all in this one area. It appeared as if this practice had been going on for years, judging by the number of bottles.

We had the windows down and were waiting for a tow truck. The driver said on the phone that he thought he knew where we were. That was a relief. The dispatcher said she had no idea where we could be. But the driver said he’d be there in an hour or so.

The dad in the SUV walked around to the back door of his vehicle and he looked over at us and nodded slightly, hesitatingly, I thought at the time. We just stared back at him in that heat-soaked way.

Our trip had been effortless until just a few miles back.

The idea was that Blake and I would pack the family’s 1993 Volvo with as much stuff as possible, then drive it from San Diego to Kansas City, where he  and his wife were starting the next chapter of their lives together. We would leave the car with him and I would fly home. Who wouldn’t want a 19-year-old car with almost 250,000 miles on it?

and his wife were starting the next chapter of their lives together. We would leave the car with him and I would fly home. Who wouldn’t want a 19-year-old car with almost 250,000 miles on it?

He and Amy had been living in Central America teaching school, both in Honduras and Guatemala. They were married in the U.S., but then left right away for their jobs, so a lot of their shower presents were still in our garage, and a lot of stuff from Blake’s room in our house was still here.

It was something to see him go through all that had collected over the past 25 years. My wife and I said a few things could go in the attic. But mostly, his choices were “keep, toss or give away.” A lot got tossed.

The night before we left, we packed the car carefully, using every centimeter for books, belongings, presents, the light saber, the large bunny costume head strategically placed so it looked out of the rear passenger window, the bike on the rack outside the trunk.

Our next door neighbor wandered over and asked about our route. We told him we were going to spend the first night in Vegas, where we had tickets for a show at the Bellagio. Then we were going to drive to Denver and spend another night, then drive to Kansas City on the third day.

“We just spent a ton of money on this car so it would make it over the mountains,” I said. “The mechanic said it would run forever.”

“Well, I hope it does better than mine when I took my daughter on that same route,” he said. “Her little four-cylinder car would slow down to 25 miles per hour whenever we’d head up hill. We barely made it.”

I felt my stomach tighten a bit.

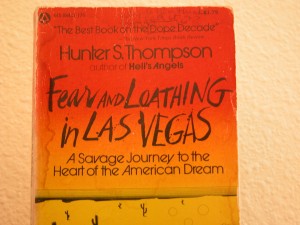

When we drove through Barstow, Blake pulled out his copy of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, and read the first several pages out loud. Barstow  figures in the opening sentence. That started a conversation about the genius, then the demise, of Hunter S. Thompson. That’s why trips like this are good. When else would he and I discuss something like that?

figures in the opening sentence. That started a conversation about the genius, then the demise, of Hunter S. Thompson. That’s why trips like this are good. When else would he and I discuss something like that?

The car started lurching a few miles past Baker. Then it died. We stood on the side of the highway for a while, trying to collect our thoughts, while cars and semi-trucks blew past, staggering us with each hot blast. Then we started it up again and drove a few more miles, when it lurched, gasped and died again. We had enough momentum to pull off this time, onto a slab of pavement where trucks could pull over and, apparently, toss urine cocktails out the window.

The dad reached in the back seat of the SUV and produced a toddler. I estimate she was about three. He stood her in the doorway and pulled down her pants. Then he turned his back to us – he was only a few feet in front of us – and held her aloft between his knees. The only part of her we could see was her bare bottom as she pooped right there on the pavement. We could only speculate as to what the conversation in the SUV had been leading up to that moment. Something had convinced him that she really couldn’t hold it.

When she was done, the dad pulled out a paper towel, wiped the girl, tried to gather as much of the mess on the pavement as he could, then tossed it over with the bottles. He put the girl back in her car seat, climbed back in the front, and drove off.

It was God saying, “Here’s what I think of your car.”

END OF PART ONE

…been there, done that.